|

|

|

|

Daniel R. Cooley Introduction.

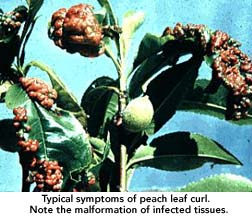

Probably the most irritating thing about seeing the

characteristic warty red leaves of peach leaf curl is

realizing that it's already too late to do anything about

the disease. The second most irritating thing is realizing

that a single fungicide treatment would, in all likelihood,

have prevented the outbreak. And to really frustrate

growers, the disease often fails to appear for years, even

without fungicide treatments, only to suddenly appear in

epidemic proportions during a particularly wet, cool

spring. Disease Cycle. The

fungus that causes peach leaf curl (Taphrina

deformans) survives as spores in microscopic crevices on

the tree. Spores from old infections lodge in loose bud

scales and other tiny fissures, waiting for the next spring.

Then, spores that are washed into buds or onto the first new

leaves will cause infections if leaves stay wet and

temperatures are between 50º and 70º F. Wet, cool

springs keep peach growth slow, so new buds and leaves

remain susceptible for a long time, and heavy leaf-curl will

develop in untreated peaches. A warm spring, even if it is

wet, won't produce nearly as much disease. Once the fungus is in the leaf tissue, fungicides won't

effect it. Infected leaves characteristically have reddened

warts or curling. Leaves may also appear yellow, orange or

purple. Infections of the new twig tissue cause swelling. In

rare instances, fruit may be infected, and develop raised,

wart-like growths. As the leaf infections age, they turn gray and appear

powdery. The fungus produces spores, which break through the

leaf surface, causing the powdery appearance. These spores

don't cause new infections, but rest in protected areas on

the peach tree until the next. Infected leaves generally

drop in early summer. Treatment. Leaf curl

is relatively easy to prevent, even though the timing of the

treatment is a little inconvenient. A fungicide spray

applied in the autumn after at least 90% leaf-fall, or in

the spring just prior to bud-swell, will generally stop leaf

curl. If an orchard has been heavily diseased, making both

fungicide applications may be necessary to deal with the

large amount of inoculum. The fungicide applications should

not be concentrated to more than 2X, to insure that the

coverage is thorough. Fungicides need to penetrate the

microscopic crevices that are protecting the fungal

spores. The most effective fungicides are chlorothalonil (Bravo)

or copper compounds (Kocide, COCS, etc.). Ziram, lime sulfur

or Bordeaux are useful but somewhat less effective. Check

the label for rates and other use recommendations. For the growing season when a leaf curl epidemic hits,

the only treatment is to minimize stress on the infected

trees. After infected leaves drop, peaches will generally

produce new leaves. This new growth stresses the tree. In

severe cases canker infections develop more easily and trees

may fail to develop adequate winter hardiness. Severe leaf

curl can ruin one season's crop, and may set the stage for

more long-term problems related to stress. Minimize the

stress by supplying some extra fertilizer, particularly

nitrogen, irrigating, and removing the fruit load. [Photo

Michael Ellis, Dept. of Plant Pathology, Ohio State

University]

Department of Microbiology

University of Massachusetts

Amherst, MA 01003

UMass Extension Factsheet F-200 Issued by UMass Extension, Stephen Demski, Director, in furtherance of the acts of May and June 30, 1914. The University of Massachusetts offers equal opportunity in programs and employment.

F-200-E

|

|